Ohio Baha’i Offerings: Unity/Oneness/Beauty of Diversity/Elimination of Racial Prejudice /Baha’i Writings | More Race Related Resources | Baha’i Writings on Justice | Race Amity Work 1910- 1921 | Universal Emancipation Proclamation / 80 articles on Black History in the Baha’i Faith | Reflecting on the Life of Abdu’l-Baha | Abdu’l-Baha Visits Cleveland and Cincinnati | Early Black Baha’is & Race Amity | Racial & Economic Justice and Other Global Issues | Contemporary Black Baha’i Scholars, Authors and Artist on the Web

Abdu’l-Baha’s Call for Race Unity in America – 1912

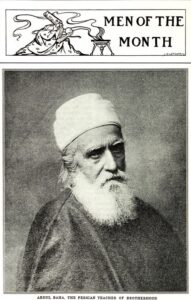

Following the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, Abdu’l-Baha – the eldest son of Baha’u’llah and His appointed successor as head of the Baha’i Faith – was freed after more than half a century of exile and imprisonment. Immediately, He began to plan how to present, in person, the Baha’i teachings to the world beyond the Middle East. [1]

For 239 days, from 11 April to 5 December 1912, ‘Abdu’l-Baha traversed the north American continent, continuing an extraordinary journey that had already taken him to Egypt, England, France, and Switzerland. [1] He called on America to become a land of spiritual distinction and leadership and gave a powerful vision of America’s spiritual destiny — to lead the way in establishing the oneness of humanity. [2]

Abbas Effendi — known as Abdu’l-Baha or “the Servant of God” — was feted by the press in both Europe and the U.S. as a philosopher, a peace apostle, even the return of Christ. Every major newspaper in New York covered his arrival on April 11 and his eight-month coast-to-coast tour that followed. This turbaned foreigner in “oriental robes” was front-page news. One headline, following his talk at Stanford University, read: “Prophet Says He Is Not A Prophet.” [5]

The New York Times reported that his mission was “to do away with prejudices…, prejudice of nationality, of race, of religion.” The article also quotes him directly: “The time has come for humanity to hoist the standard of the oneness of the human world, so that dogmatic formulas and superstitions may end.” [5]

America in 1912, nearly 50 years after the Emancipation Proclamation that freed every slave, was decades away from realizing ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s vision of racial equality.

African-Americans, although now freed from oppressive slavery, were almost universally regarded as lesser than whites. The so-called “Jim Crow” segregation laws had gained impetus from an 1875 Supreme Court ruling that the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution did not protect any Black person from discrimination by private businesses and individuals, but only from discrimination by states. So a racial caste system existed in the United States, reinforced from the pulpits of many of America’s churches, and pronounced as evident truth by scientists, phrenologists, and Social Darwinists, who claimed that persons of color were innately inferior both intellectually and culturally to whites. [4]

‘Abdu’l-Bahá challenged America to go beyond tolerance, to embrace diversity completely, and to demolish racial barriers in law, education and even marriage.[4]

Throughout his U.S. visit, he swept aside the social protocol of segregation by insisting that every place where he spoke be open to people of all races. In New York City at the Great Northern Hotel on 57th Street, where a banquet had been arranged in his honor, the manager vehemently refused to allow any blacks on the property. Abdu’l-Baha remedied the situation by hosting a second banquet the following day at the home of one of his followers, with many whites serving blacks — a subversive, even dangerous notion at the time. [5] Special Meeting for Black Baha’is

Abdu’l-Baha’s talks pierced audiences with a radical simplicity. And yet he advanced ideas that Americans still wrestle with a century later: the need for true racial harmony and gender equality; the elimination of extreme wealth and poverty; the dangers of nationalism and religious bigotry; and an insistence upon the independent search for truth. [5]

During ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s travels, He “met with people of diverse backgrounds in both private and public settings, often giving talks to hundreds of people. And everywhere He went, He spoke about the oneness of humanity…” [1] He always delivered a strong and unmistakable call for racial integration and unity.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá demonstrated His vision of racial equality by bold and unconventional actions from His first days in America. In Washington, D.C., He set the tone at a luncheon in His honor on April 23, 1912, held at the home of a prominent Persian diplomat, who was also a Bahá’í. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá took His place, looking around the elegant dining room at the white faces, everyone seated according to rank and social position and in keeping with strict Washington social protocol. He then stood up and asked his host, “Where is Mr. Gregory? Bring Mr. Gregory.” The embarrassed host had no choice but to hastily rearrange the place settings and make room for the extra guest, African-American attorney Louis Gregory, who had escorted ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to the diplomat’s house from Howard University where He had just spoken. Mr. Gregory was quietly taking his leave. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá insisted that he join the party and occupy the honored place to His right at the head of the table. Thus, in a single stroke, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá defied Washington protocol and swept aside the practice of segregation by race and categorization by social rank, setting a powerful example and challenging the customs of the deeply divided capital city. [4]

The overflowing crowd in Rankin Chapel at Howard University that afternoon was the first predominantly black audience ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would address in America, and the first of two such meetings that Louis Gregory had arranged for that day. [2]

Reverend Wilbur Patterson Thirkield, Howard’s eighth President, introduced ‘Abdu’l-Bahá…“and here, as everywhere when both white and colored people were present, ‘Abdul-Baha seemed happiest. The address was received with breathless attention by the vast audience, and was followed by a positive ovation and a recall.” [2]

‘Abdu’l-Bahá stated unequivocally that skin color was of no importance before God, except as an adornment and a source of charm. Only among humans, He emphasized, had skin color become a cause of discord. [4]

“Animals, despite the fact that they lack reason and understanding, do not make colors the cause of conflict. Why should man, who has reason, create conflict? This is wholly unworthy of him.” [4] Talk at Howard University

In this same talk, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá praised the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 as paving the way for universal and worldwide emancipation of persons of color, and emphasized the even higher goal for which this nation must strive, that of love, unity and complete integration between the races. [4]

‘Abdu’l-Bahá would refer to the Civil War in mixed race gatherings in New York and Washington, highlighting the importance of the sacrifices made, and calling upon both blacks and whites to continue the arduous work of setting aside all traces of prejudice, and committing themselves to wholehearted integration. [11]

On Tuesday, April 30…Jane Adams welcomed ‘Abdu’l-Baha to Hull House and introduced Him to an audience that far exceeded the auditorium’s seating capacity of 750. [10] He used the opportunity to speak of the power of the love of God to transform society. [7]

He states that between all people there are things they share in common and things in which they differ. When the things they share overcome those in which they differ, there is unity and concord. When those in which they differ overcome those they share, then there is disunity and strife. Color is one of these points of difference. And even though it is very small, many people often let it take precedence over all those other things. ‘Abdu’l-Baha then goes on to offer a remedy. [7]

“But there is a need for a superior power to overcome human prejudices, a power which nothing in the world of mankind can withstand and which will overshadow the effect of all other forces at work in human conditions. That irresistable power is the love of God. It is my hope and prayer that it may destroy the prejudice of this one point of distinction between you and unite you all permanently under its hallowed protection.” (PUP 68) [7] Talk at Hull House, Chicago

From Hull House He went by car to Handel Hall to speak to the Fourth Annual Convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which had been discussing lynchings and job and housing discrimination. [10]

‘Abdu’l-Bahá began his address at Handel Hall by quoting the Old Testament: “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.” “Let us find out,” he proposed, “just where and how he is the image and likeness of the Lord, and what is the standard or criterion whereby he can be measured.” [3]

Then he asked a series of rhetorical questions: “If a man should possess wealth, can we call him an image and likeness of God? Or is human honor the criterion whereby he can be called the image of God? Or can we apply a color test as a criterion, and say such and such a one is colored a certain hue and he is therefore, in the image of God? [3]

“Hence we come to the conclusion that colors are of no importance. Colors are accidental in nature. . . Man is to be judged according to his intelligence and spirit. . . That is the image of God.” [3] Talk at 4th Annual Conference of NAACP

Almost immediately across the road from Handel Hall, at the Masonic Temple at 29 East Randolph Street, another convention was underway that evening. Fifty-eight delegates from forty-three cities were about to elect nine members to the governing board of the Bahá’í Temple Unity, a national body formed to coordinate the largest project ever undertaken by the Bahá’ís in North America: the construction of an enormous house of worship north of Chicago… [3] (‘Abdu’l-Baha would also address this audience of around 1,000 saying that this temple was founded for the unification of mankind.)

After the first round of voting [by secret ballot] there was a tie for ninth place between Frederick Nutt, a white doctor from Chicago, and Louis Gregory, the black lawyer from Washington, DC. In a dramatic departure from the vicious 1912 Presidential election, which raged all around them, each man resigned in favor of the other. [3]

Then Mr. Roy Wilhelm, a delegate from Ithaca, NY, stood and put forward a proposal. His motion, seconded by Dr. Homer S. Harper of Minneapolis, recommended that the convention accept Dr. Nutt’s resignation. [3] The delegates responded unanimously. [3]

To have elected an African American to the governing board of a national organization of largely middle- and upper-class white Americans — and to have done so at the nadir of the Jim Crow era in 1912 — was rare in the extreme. Even the NAACP had only elected one black member to its executive committee when it had been formed in 1909. [3] ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s assault on the color line was beginning to bear fruit. [3]

During Louis Gregory’s visit to Alexandria in 1910, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had begun to craft a new language of race — a new set of racial images and metaphors — which consciously contradicted ingrained, popular Social Darwinist associations. [2]

They took Louis Gregory as their subject. “I liken you,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told him, “to the pupil of the eye. You are black and it is black, yet it becomes the focus of light.” “When he went to Stuttgart,” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá wrote of him, “although being of black color, yet he shone as a bright light in the meeting of the friends.” “He will return to America very soon,” he advised an American friend, “and you, the white people, should then honor and welcome this shining colored man in such a way that all the people will be astonished.” [2]

At Howard University, at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church and in his other speeches to mixed-race gatherings in Washington ‘Abdu’l-Bahá deepened and extended this racial language in order to recast racial differences as a source of beauty. [2]

“As I stand here tonight and look upon this assembly” he told one audience, “I am reminded curiously of a beautiful bouquet of violets gathered together in varying colors, dark and light.” And to others: “In the vegetable kingdom the colors of multicolored flowers are not the cause of discord. Rather, colors are the cause of the adornment of the garden because a single color has no appeal; but when you observe many-colored flowers, there is charm and display. The world of humanity, too, is like a garden, and humankind are like the many-colored flowers.”

Talk at Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church, Washington D.C.

“In the clustered jewels of the races may the blacks be as sapphires and rubies and the whites as diamonds and pearls. The composite beauty of humanity will be witnessed in their unity and blending.” [2] Talk at Home of Mrs. Andrew J. Dyer, Washington D.C.

W. E. B. Du Bois characterized this seemingly innocent approach to the race issue as “the calm sweet universalism of Abdul Baha.” But ‘Abdu’l-Bahá harbored no illusions about the systemic crisis that the race problem posed for America’s social fabric. The problem was urgent, and required immediate, systematic intervention: [2]

“Until these prejudices are entirely removed from the people of the world,” he wrote, “the realm of humanity will not find rest. Nay, rather, discord and bloodshed will be increased day by day, and the foundation of the prosperity of the world of man will be destroyed.” “Now is the time for the Americans to take up this matter and unite both the white and colored races. Otherwise, hasten ye towards destruction! Hasten ye toward devastation!” “Indeed, there is a greater danger than only the shedding of blood. It is the destruction of America.” [2]

On the other hand, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá put little faith in the ability of legal and political equality alone to remove underlying race hatred. “You may bring all the physical powers of the earth,” Kate Carew had heard him say, “and try by their means to make a union where all will love each other, where all will have peace — but it will end in failure.” A year later he wrote to Andrew Carnegie, who had given ‘Abdu’l-Bahá a copy of his book, The Gospel of Wealth. “‘Human Solidarity,’” he wrote, “is greater than ‘Equality.’ ‘Equality’ is obtained, more or less, through coercion (or legislation) but ‘Human Solidarity’ is realized through the exercise of free will.” [2]

It was not enough for antagonistic racial groups to be forced together through legislative means: they had to want to unite. [2]

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s advocacy for social equality, therefore, went beyond the purely economic, political, and moral aspects of the race issue. He neither lined up with any of the popular white positions in the American racial debate, nor accepted the dichotomy between appeasement and political agitation that characterized the thought of African American leaders. [2]

Unlike Booker T. Washington and the Social Gospel reformers, who preoccupied themselves with economic development; unlike Du Bois’s focus on political rights and race pride; and unlike other radicals, such as Clarence Darrow, who opposed segregation and social inequality on the grounds that they violated American liberty, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sought to change the emotional posture of white and black Americans toward the race issue and toward each other. [2]

Louis Gregory wrote to W.E.B. Dubois in the 1930s, stating that the new religion was the means of transforming hearts and erasing racism: “Were the Bahá’í Faith merely a cult with a human origin, it could attract only people who shared its views. Its mysterious Power is indicated by its ability to transform people whose views are diametrically opposed to its ideals and to give them new minds and new hearts.” [4]

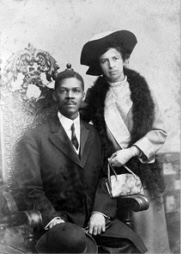

In further defiance of convention, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged the marriage of Louis Gregory and a white English Bahá’í, Louisa Mathew, whose pilgrimage in 1911 had coincided with Gregory’s and who had traveled to America with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá at His invitation. Although ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had raised the topic of intermarriage during their visit to Egypt, telling Gregory, “If you have any influence to get the races to intermarry, it will be very valuable,” at first they thought of each other only as friends. When they met again in America, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá urged them to consider their relationship in a new light. Only then did the potential attachment He had sensed between them blossom into love. They were married in a quiet ceremony in New York City on 27 September 1912, becoming the first interracial Bahá’í couple at a time when intermarriage in the United States defied popular scientific theories about the baneful effects of “race mixing,” flouted the customary dictates of a divided society, and was a criminal offense in much of the nation. [6]

‘Abdu’l-Bahá encouraged interracial marriage as a way to unite the races quite literally, saying that such marriages would produce strong and beautiful offspring, children who are both clever and resourceful. [4]

Again concerning interracial marriage:

After the party of pilgrims returned to Egypt from Haifa and Akka, ‘Abdu’l-Baha stressed once again the importance of racial unity. In the presence of a roomful of followers, He addressed to one of the outstanding European-Descent American Baha’is in Washington a letter (what Baha’is term a Tablet), regarding racial segregation:

You have written that there were several meetings of joy and happiness, one for white … another for colored people. Praise be to God! As both races are under the protection of the All-Knowing God, therefore the lamps of unity must be lighted in such a manner in these meetings that no distinction be perceived between the white and colored. Colors are phenomenal; but the realities of men are Essence. When there exists unity of the Essence what power has the phenomenal? When the Light of Reality is shining what power has the darkness of the unreal? If it be possible, gather together these two races, black and white, into one assembly and put such love into their hearts that they shall not only unite but even intermarry. Be sure that the result of this will abolish differences and disputes between black and white. Moreover by the will of God, may it be so. This is a great service to the world of humanity.

After dictating this Tablet, Mr. Gregory recalled, “’Abdu’l-Baha took a vessel containing blackberries and gave some of these to each of the friends present.”

Undoubtedly, Louis Gregory recognized that ‘Abdu’l-Baha dictated His statement not only to the Baha’is in Washington but also to those followers who were in His presence that day. Among the latter He then chose to reinforce His words about race by the symbolic sharing of the delicious, black-colored fruit. But, as Louis Gregory, and his fellow pilgrim Louisa Matthew were later to realize, the Master’s motives were more complicated still. He never explained why He had delayed Mr. Gregory’s pilgrimage; but it soon became clear that, whether ‘Abdu’l-Baha had deliberately brought Louis and Louisa together, He had henceforth envisioned for them “a great service to the world of humanity.”

‘Abdu’l-Baha had instructed the DC community to integrate meetings begining in March of 1910 making DC, the first racially integrated Baha’i Community in North America. This permitted, by the end of the Master’s visit, one of the foremost National African Descent newspapers, the ‘Washington Bee’ to report from Washington, that the Baha’i Faith’s “white devotees, even in this prejudice-ridden community, refuse to draw the color line. The informal meetings, held frequently in the fashionable mansions of the cultured society in Sheridan Circle, Dupon Circle, Connecticut and Massachusetts avenues, have been open to Negroes on terms of absolute equality.” [9]

It was following His return to the Holy Land, however, and after the world war that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá set in motion a plan that was to bring the races together, attract the attention of the country, enlist the aid of famous and influential people and have a far reaching effect upon the destiny of the nation itself. [8]

Mrs. Agnes Parsons, a prominent Washington D.C. socialite, was tasked with planning America’s first Race Amity Conference in 1921. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told Mrs. Parsons in 1920 on her visit to the Bahá’í Holy Places in Haifa, Israel, that she must organize a convention in her city to unite the races. This admonition followed closely on the heels of widespread racial tension across the country, called the “Red Summer” of 1919. During July 1919, white servicemen returned from the war fronts and attacked Black people. It turned into race warfare in Washington, D.C. when white gangs attempted to burn the black district, prompting its residents to arise to defend themselves and their property. It was into this environment, and against the separatism of Marcus Garvey, that Mrs. Parsons and Louis Gregory were thrust forth by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to plan an event that advanced the principle of racial equality, and that aimed at expanding the nation’s thinking to embrace not merely tolerance, but racial harmony and amity. Four Race Amity conferences were held between 1921 and 1924, an historic achievement by American Bahá’ís. [4] First Race Amity Conference in Washington D.C. May 1921

The workers had unusual experiences and the spirit of reconciliation seemed to sweep the city. This convention had the fervent approval of the President of the United States although officially he took no part in it. The gratitude of the chief executive may be well understood when it is recalled that but a short time before, that historic city had been violently disturbed by a race riot fatal to many. Now the cleansing and purifying power of the Holy Spirit was at work bringing harmony and peace to those who had passed through the shadows of death. [8]

‘Abdu’l-Baha had sent a message to this convention: “Say to this convention that never since the beginning of time has one more important been held. This convention stands for the oneness of humanity…There is only one love which is unlimited and divine, and that is the love which comes with the breath of the Holy Spirit — the love of God — which breaks all barriers and sweeps all before it.” [8]

From a talk given by ‘Abdu’l-Baha at the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington D.C.:

“The truth is that God has endowed man with virtues, powers and ideal faculties of which nature is entirely bereft and by which man is elevated, distinguished and superior. We must thank God for these bestowals, for these powers He has given us, for this crown He has placed upon our heads.”

“How shall we utilize these gifts and expend these bounties? By directing our efforts toward the unification of the human race. We must use these powers in establishing the oneness of the world of humanity, appreciate these virtues by accomplishing the unity of whites and blacks, devote this divine intelligence to the perfecting of amity and accord among all branches of the human family so that under the protection and providence of God the East and West may hold each other’s hands and become as lovers. Then will mankind be as one nation, one race and kind — as waves of one ocean. Although these waves may differ in form and shape, they are waves of the same sea. Flowers may be variegated in colors, but they are all flowers of one garden. Trees differ though they grow in the same orchard. All are nourished and quickened into life by the bounty of the same rain, all grow and develop by the heat and light of the one sun, all are refreshed and exhilarated by the same breeze that they may bring forth varied fruits. This is according to the creative wisdom. If all trees bore the same kind of fruit, it would cease to be delicious. In their never-ending variety man finds enjoyment instead of monotony.” ~ Promulgation of Universal Peace

’Abdu’l-Baha (1844-1921), eldest son of Baha’u’llah and His chosen successor, was known as an ambassador of peace, a champion of justice, and the leading exponent of a new Faith. He was awarded a knighthood by the British Mandate of Palestine for his humanitarian efforts during WWI. Through a series of epoch-making travels to Africa, North America and Europe, `Abdu’l-Bahá–by word and example–proclaimed with persuasiveness and force the essential principles of his Father’s religion. Upon his death ten thousand people–Jews, Christians, and Muslims from all denominations–gathered on Mount Carmel in the Holy Land to mourn his passing.

Today around the world there are millions of people — from every country, language, and background — for whom Abdu’l-Baha’s example is central to their lives.

Documentary: ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s Initiative on Race from 1921: Race Amity Conferences

‘Abdu’l-Baha in Modern American History Some thoughts on why ‘Abdu’l-Bahá has eluded American historians in their studies of the Progressive Era.

On February 1, 2012, Cornel West, Professor of African American Studies and Religion, Princeton University, paid tribute to the historic Baha’i efforts to foster ideal race relations in America:‘When you talk about race and the legacy of white supremacy, there’s no doubt that when the history is written, the true history is written, the history of this country, the Baha’i Faith will be one of the leaven in the American loaf that allowed the democratic loaf to expand because of the anti-racist witness of those of Baha’i faith.’ If and when, as suggested by Cornel West, a revisionist history of the Jim Crow era is written, the contribution of the Baha’i ‘race amity’ initiatives–envisioned and mandated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá himself–should take its rightful place in the annals of American history.

The Baha’i Race Amity Movement and the Black Intelligentsia in Jim Crow America: Alain Locke and Robert S. Abbott Christopher Buck Pennsylvania State University

This study demonstrates how the Baha’i ‘Race Amity’ efforts effectively reached the black intelligentsia during the Jim Crow era, attracting the interest and involvement of two influential giants of the period – Alain Leroy Locke, PhD (1885–1954) and Robert S. Abbott, LLB (1870–1940). Locke affiliated with the Baha’i Faith in 1918,2 and Abbott formally joined the Baha’i religion in 1934. Another towering figure in the black intelligentsia, W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) – whose first wife, Nina Du Bois (d. 1950), was a member of the New York Baha’i community – had sustained, for a period of time, consider- able interest in the Baha’i movement, as documented in a forthcoming special issue of the Journal of Religious History, guest edited by Todd Lawson.3 These illustrious figures – W. E. B. Du Bois, Alain L. Locke and Robert S. Abbott – are ranked as the 4th, 36th and 41st most influential African Americans in American history.4 It is not so much the intrinsic message of the Baha’i reli- gion that attracted the interest of the black intelligentsia, but rather the Baha’i emphasis on ‘race amity’ – representing what, by Jim Crow standards, may be regarded as a socially audacious – even radical – application of the Baha’i ethic of world unity, from family relations to international relations, to the prevailing American social crisis.

See A Vision of Race Unity

For an account of the dedication to Race Unity of the Baha’i community and it’s Institutions since the time of ‘Abdu’l-Baha and an overview of the important and central role Black Americans have historically played in the development of the American Baha’i community. This site also has a statement on: Privileging of Black/White Aspect of Race Unity:

Also:

A Black Rose and a Black Sweet New York 1912. A sweet story about how ‘Abdu’l-baha singled out the one black child, in a room full of children from the Bowery district of New York, for special attention.

Washington D.C. – The First Racially Integrated Baha’i Community in North America – 1910

African American Baha’is During ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s Lifetime

Public Talks of ‘Abdu’l-Baha in America

The Way of the Master / George Townsend reflects upon ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s character and the lessons and example He offered for the lives of people everywhere. – To live today in deed and truth the kind of life that Jesus of Nazareth lived and bade his followers lead; to love God wholeheartedly and for God’s sake to love all mankind even one’s slanderers and enemies…

How Indian cavalrymen rescued Bahai spiritual leader during World War I Alarmed by the growing popularity of Abdu’l Baha and his humanitarian and religious activities, the Turkish commander-in-chief threatened to crucify Abdu’l Baha on Mount Carmel in Haifa and destroy all the shrines of the Bahai faith as soon as the Ottomans won the war. A group of Indian soldiers, fighting under British General Edmund Allenby, rescued Abdu’l Baha from Ottoman captivity in September 1918, in the last major cavalry campaign in military history.

The above article on ‘Abdul-Baha was compiled by Susan Poppa Tower from the following resources:

[1] http://news.bahai.org/story/918

[2] http://239days.com/2012/04/23/this-shining-colored-man

[3] http://239days.com/2012/04/30/the-fallout-from-a-city-in-flames

[4] http://centenary.bahai.us/stopping-racism-america

[5] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rainn-wilson/abdul-baha_b_1419099.html

[6] http://www.bahai-encyclopedia-project.org

[7] http://bahaicoherence.blogspot.com/2010/05/social-action-and-love-of-god…

[8] Baha’i World Volumes, Volume 7, p. 655 -656

[9] http://www.dcbahaitour.org/place/?id=38 Mrs. Pocahontas Pope’s House

[10] 239 Days, ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s Journey in America / Allan Ward

[11] http://239days.com/2012/11/28/a-nation-shaped-by-sacrifice/